October 26, 2020

Dual-organ system enables the measurement of cardiac toxicity arising from breast cancer chemotherapy

(LOS ANGELES) – Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer for women around the world, and much effort has been spent in the development of therapies to treat this disease. Among these treatments, chemotherapy has been shown to be among the most effective methods; however, the drugs used in these therapies can have adverse side effects, the most serious of which is toxicity to the heart. In addition to tissue damage to the heart, chemotherapeutic breast cancer drugs can also affect the heart’s pumping ability or result in clinical heart failure.

In order to avoid these problems, efforts are made to monitor the heart of patients who are undergoing chemotherapeutic treatment for breast cancer and to adjust their treatment levels accordingly. Current methods to monitor the heart include the use of echocardiograms and other imaging procedures, as well as taking biopsies of the heart. But the imaging methods only detect late-stage, irreversible cardiac failure and biopsies are highly invasive and are physically painful for the patient.

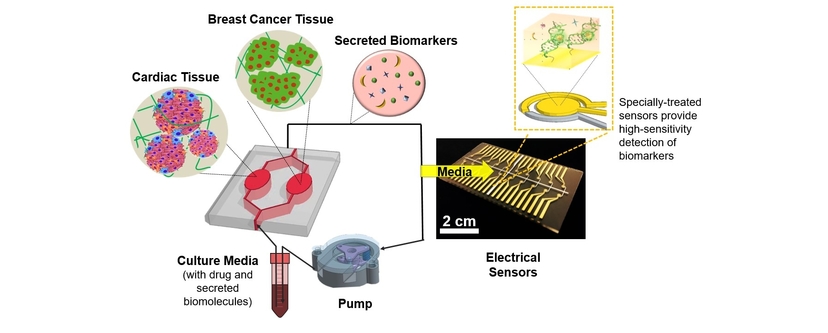

There are alternative monitoring systems that can be created in the laboratory to mimic what is happening in the body. These organs-on-a-chip models consist of a silicone chip with compartments for culturing specific types of live human tissues. The compartments are connected to microfluidic channels through which oxygen and nutrient media are pumped and circulated. The tissue cells normally secrete molecules called biomarkers into the surrounding medium, which are good indicators of their health and function. The levels of these biomarkers can then be measured in order to determine the condition of the tissues.

Recently, methods have been successful in creating simple systems to monitor heart toxicity from breast cancer drugs in selected patients, but, to date, there have been few attempts to produce such a system in a larger, more comprehensive and reliable model.

A collaborative team, which includes a group from the Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation, has developed an organs-on-a-chip system that more widely examines the responses of breast cancer and heart tissues to therapeutic breast cancer drugs. For their system, they chose to measure two cardiac biomarkers which are produced by healthy heart cells and one biomarker that is produced by actively growing breast cancer cells. Included in the study were tests of both healthy and artificially-induced damaged heart tissues, to mirror the possible heart conditions of breast cancer patients prior to chemotherapy. They also devised added features to the system to enhance its capabilities.

The team designed a chip system with two separate compartments for tissue cultures of breast cancer and either healthy or artificially-induced damaged heart tissues; these compartments were connected by channels which allowed the free flow of fluid between them. To more closely reproduce the mechanical properties of native body tissues, the tissue cultures were prepared by enclosing tiny spheroids of either heart or breast cancer cells in a gelatinous substance. Pre-determined controls for the chip’s circulatory fluidic system ensured that the tissues received oxygen, nutrient media and chemotherapeutic drug delivery.

“This work establishes an important model for monitoring cardiac toxicity from breast cancer chemotherapy,” said first author Junmin Lee, Ph.D., part of the Terasaki Institute’s research team. “We successfully created cardiac and breast cancer tissues that closely mimic bodily tissues, and we developed an improved sensing device and drug delivery system; these are milestones in organs-on-a-chip technology.”

In comparison with single-compartment models with either heart or breast cancer tissues, it was found that actively growing breast cancer tissues in communication with heart tissues decreased the levels of healthy heart biomarkers than those found in the single chip systems. Moreover, the dual chip system provided evidence that the breast cancer cells’ biomarker secretion was affected not only by drug treatment, but by their interaction with cardiac tissues with different levels of damage. This showed that the interplay between the heart and breast cancer tissues had an important influence on indicators of cell function and disease progression.

Although no definitive conclusions could be made on whether pre-damaged heart tissues were more susceptible to cardiac injury when exposed to breast cancer drugs, the results showed that in healthy cardiac tissues, delivery of the breast cancer drug resulted in decreased cellular growth and secretion of healthy heart biomarkers than without the drug.

Further tests may be conducted to explore the use of this model for detecting and predicting cardiac toxicity from chemotherapeutic drugs. The model may be expanded to include observations of tissues cultured on a long-term basis, examination of additional biomarkers, testing the model using tissues derived from several patients and measurements of other, non-biomarker indicators of cardiac damage (electrical and contractive functions, for example). Future possibilities could be the addition of a liver tissue component onto the chip and considerations of the system’s scalability to correlate with bodily systems.

“These efforts lay important groundwork that can pave the way to future applications in disease modeling,” said Ali Khademhosseini, Ph.D., director and CEO for the Terasaki Institute. “The Personalized Physiological platform that we have at our Institute is one of the many vehicles that we have for bringing personalized medicine to the real world.”